Concept and Goals

Each individual cuneiform text opens up a specific insight into the world of ancient Mesopotamia. We encounter people and their things in everyday life, follow a legal case or immerse ourselves in religious poetry. A written object at the same represents time a find from a particular building, is a testimony to a dialect and follows certain textual patterns. For each cuneiform artefact preserves practices from the world in which it was created. Modern scholarship reawakens the information stored in a document, constantly recovering new facets of a sunken and fascinating world.

Cuneiform Texts and Their Context

The most common writing medium for cuneiform was a lump of clay (“tablet”), on which the characters of the cuneiform script were incised with a reed stylus. Objects made of dried or ovenfired clay easily survive in the arid climates of the Middle East, and the cuneiform material constitutes therefore one of the most voluminous text corpora of antiquity.

All artefacts inscribed in cuneiform originate from ancient sites where they had been either deliberately deposited or intentionally discarded. The texts were typically deposited close to where they had been read, and this location often corresponds to their place of writing. Textual information, together with the artefacts’ location, allows conclusions about the institutional context of their creation, indicating whether we are dealing e.g. with a family archive in a private house, or a temple’s tablet deposit of ritual and scholarly compositions. If the find situation is documented archaeologically, it is normally possible to reconstruct the social context in which a document was written and received. Therefore, the find context and the analysis of the materiality of the artefacts offer decisive clues for reconstructing Mesopotamian practices concerning writing and written documents.

The Collections of the Iraq Museum

The artefacts kept in the Iraq Museum originate from excavations conducted after 1926, and once the division of finds between Iraq and the foreign archaeological missions had come to an end in 1936, all excavated objects have been kept here, together with their excavation records: the necessary information for an analysis based on the text’s specific situation is, therefore, available. The cuneiform artefacts in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad are therefore an ideal dataset to understand the role that cuneiform texts played in the ancient societies that produced them. The Iraq Museum houses cuneiform texts of all types, dating across the entire chronological range of “cuneiform culture”, from the Chalcolithic to the Parthian periods, from the fourth millennium BCE to the 1st century AD, from 85 archaeological sites with well-recorded contexts, from private houses to temples and palaces.

On the other hand, the cuneiform collection in the Iraq Museum can be described as severely understudied. Especially since the beginning of the Iraq conflict in 1990 and the subsequent decades of isolation, these materials have largely been excluded from research, their physical inaccessibility compounded by the almost complete lack of a photographic documentation.

The cuneiform texts from the Iraq Museum lend themselves to a context-based, large scale edition project due to the availability of archaeological records, and a substantial gain in knowledge that can be expected from studying this long-neglected material. In addition to the preparation of a photographic documentation in collaboration with the Iraq Museum, the project includes a programme for preserving and restoring the cuneiform artefacts. A short-term fellowship programme allows Iraqi scholars to work at BAdW on the edition of the cuneiform tablets assigned to them by the Iraqi authorities, thereby adding further material to the initial dataset of approximately 17,000 known Iraq Museum texts.

Historical, Social, and Institutional Contexts

The texts of the Iraq Museum cover a period of three millennia, ranging from the city-states of the Early Bronze Age to the age of empires in the Iron Age, and bear witness to deep social and cultural changes brought about by new religious, technological, political, and economic developments. Like other archaeological artefacts, cuneiform objects originate from concrete historical situations: within social and political orders and practices involving the artefact’s creation, use and deposition; within the material culture of specific lifestyles (including architecture, food and body practices); or within the cultural symbol systems, i.e. the world that shaped the worldviews of authors, writers and text recipients.

From Text Type to Linguistics

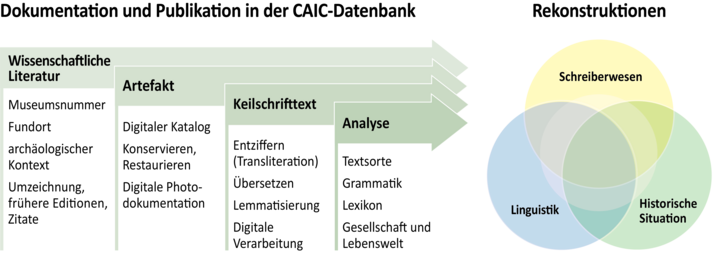

The “text type” (or “genre”) is the category that links the artefact, defined by its materiality and the archaeological find context, to the text inscribed on it (see Fig. 1). On the one hand, the chosen text type crucially defines the material form of a written medium (diplomatics). On the other, the conceptual framework of the genre also determines the linguistic form of a text. Text types form conventionalized patterns that were created, transmitted and modified as social practices enabling successful communication. Historical processes of tradition and adaptation led to constant changes. Thus, established text patterns such as the legal formulae documenting a loan could be adapted creatively to also record other types of debt obligations; and lists were used for administrative records but also for teaching cuneiform signs and vocabulary.

Genres function as conceptual, typified patterns for linguistic action on text production and reception. Accordingly, Akkadian and Sumerian texts are not simply testimonies to linguistic utterances that arrange words according to the grammar of the language. The language system (phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon) can rather be understood as resulting from a conventionalized practice of verbal action processed in cognitive processes depending on the context. Ultimately, each cuneiform text is a testimony to conventionalized language use within a certain genre that serves as a pattern of action. Text types are often characterized by a specific syntax (“Tempus” system, “if” clauses), lexicon (poetic, technical) or idiomatic phrases, sentences and sections. From a praxeological perspective, phenomena of canonical texts, such as intertextuality or the use of recurring stock phrases, can be plausibly understood as shared knowledge of the agents of writing.

Knowledge Horizons and “Lebenswelten”

The Akkadian and Sumerian lexicon used in a specific text is determined by the text’s type, especially in regard to the choice of words. But genre knowledge is only one aspect of the entire shared world knowledge of the agents of writing, the text producers and recipients, within which a lexeme semantically refers in a specific situation to the referees.

In a large-scale edition project that makes cuneiform texts of all kinds accessible in their historical setting, the reconstruction of knowledge horizons and “Lebenswelten” is also reflected in the practices of translation. Conversely, the translation, and thus primarily the lexicon, offer an important starting point for exploring and studying facets of ancient Mesopotamian life experiences and knowledge networks.

A Conceptual Framework for a 25-Years Project

Text does not speak by itself; rather, its meaning arises from linguistic, pragmatic, institutional, and historical contexts, which the specialized philologist has internalized through constant practice. In the case of cuneiform, this fact typically prevents non-specialists from reading and understanding a text, even when offered in translation. A core goal of the discipline of cuneiform studies must therefore be to make data and research results accessible to other fields of research and, by extension, to the general public. Our CIAC project is designed to contribute decisively to this end. The philological editorial work has been placed in a theoretically founded frame (see Fig. 1): against the backdrop of the Theory of Social Practices, various concepts and approaches can be fruitfully combined, such as the concepts of the historical locatedness of specific knowledge of practice and of habitus for the description of social practices, as well as artefact theories in archaeology, and in linguistics, the semantic theory based on verbal usage, linguistic pragmatics and the knowledge-structuring role of text types.

Within this theoretical framework, the project will advance further the best philological methods of cuneiform languages (see Fig. 2). In addition to decipherment and translation, the edition of an individual cuneiform text should include a discussion of the palaeographic, grammatical and lexical peculiarities, as well as an analysis of the artefact’s materiality and the historical, social and institutional contexts of its creation, use and deposition. In turn, each text contributes to the reconstruction of the usage of language and writing, thus verbal action, and the “Lebenswelten” of ancient Mesopotamia.

By taking its departure from a theory of social practices as applied to cuneiform artefacts, the project’s data compilation protocol seeks to interconnect the individual research steps in a way that stimulates team-led work. This requires collaboration on a digital online platform that facilitates all elements of the editing process. By consciously articulating the conceptual underpinnings of the project and by building them into the infrastructure of the digital platform, the team members share a common methodological context.

Key Research Questions

Reconstructing the material, social and linguistic foundations of the production of cuneiform texts represents the main goal of the project. Why were exactly these words used in a letter, and how would that content be phrased in a comparable context elsewhere in ancient Iraq, at another time? What glimpses on the contemporary world can administrative or private documents provide? What unites a set of literary texts that were found together, forming a particular “library”? Such questions will emerge anew with each archaeological site, with each text genre represented there, with each individual cuneiform artefact. In a more systematic way, such questions can be listed as follows:

- Where in Iraq, at which times, were which cuneiform texts written?

- Which media and genres were used by the people who produced cuneiform texts?

- Which linguistic expressions were considered appropriate in which textual contexts?

- How did concrete historical situations shape text production?

- How does the ancient Mesopotamian world manifest itself in the cuneiform texts?

Research Goals

The project is dedicated to digitally re-editing the approximately 17 000 texts from all periods of cuneiform culture kept in the Iraq Museum that have already been published in any form (as photograph or line drawing, with or without transliteration or translation), applying modern standards to their documentation, edition and annotation. The potential of the Iraq Museum’s rich cuneiform documentation is yet to be fully exploited.

A contextual approach is deemed crucial for providing reliable and easy access to the complex data: for historians and archaeologists, but also any other interested parties worldwide, including local Iraqi authorities, schools, cultural heritage specialists, journalists, and tour guides. The project addresses the needs of these diverse users when preparing its data and making it accessible, and thus contributes to disseminating knowledge about the early cultures of Iraq. The project’s digital environment is designed to allow interested parties easy and full access to all data while enabling the project team to keep text editions, meta-data and tools updated. The project has five interlocking research goals:

- To produce editions of all known artefacts from the Iraq Museum according to the most up-to-date Assyriological standards, with transliteration (sign-by-sign representation in Latin script), lemmatisation (grammatical and lexical tagging), and English translation, which will make this cultural heritage accessible to specialists and the wider public alike.

- To document and preserve these artefacts for future generations using cutting edge conservation and imaging techniques and sustainable data management.

- To fully contextualise (historically, socially, institutionally) these artefacts and the associated writing, reading, storing and discarding practices within a common conceptual research framework, drawing on information available for each artefacts’s archaeological context and material attributes.

- To shape the future of the discipline by nurturing the next generations of scholars. In addition, the initiative will facilitate the international dissemination of research by junior Iraqi scholars by supporting these scholars in the publication of cuneiform texts from the Iraq Museum.

- To develop a pioneering digital platform to perform this work and host the resultant data, and to make it accessible to specialists and to the wider public.

By assembling specialists for all periods and genres of cuneiform writing, CAIC will integrate specialised strands of cuneiform philology within a shared research framework and promote a holistic approach to Ancient Near Eastern studies. Furthermore, the focus on the artefacts’ materiality and contexts will produce data and results that are attractive to historians, archaeologists and scientists from related disciplines.